New X-COM book explains the special kind of terror that made the first game a classic | PC Gamer - richardsonwinget1952

New X-COM book explains the special rather terror that made the low game a classical

No series has defined the past and nowadays of ferment-based strategy more than XCOM. The Firaxis-made games in the series, XCOM: Foe Unknown and XCOM 2, are two of the best games of the last decade. The whole series, which dates back to the mid-'90s, is one of PC gaming's nigh beloved, even with its history of forcing us to make painful decisions and the impugnable third-person shooter spinoffs.

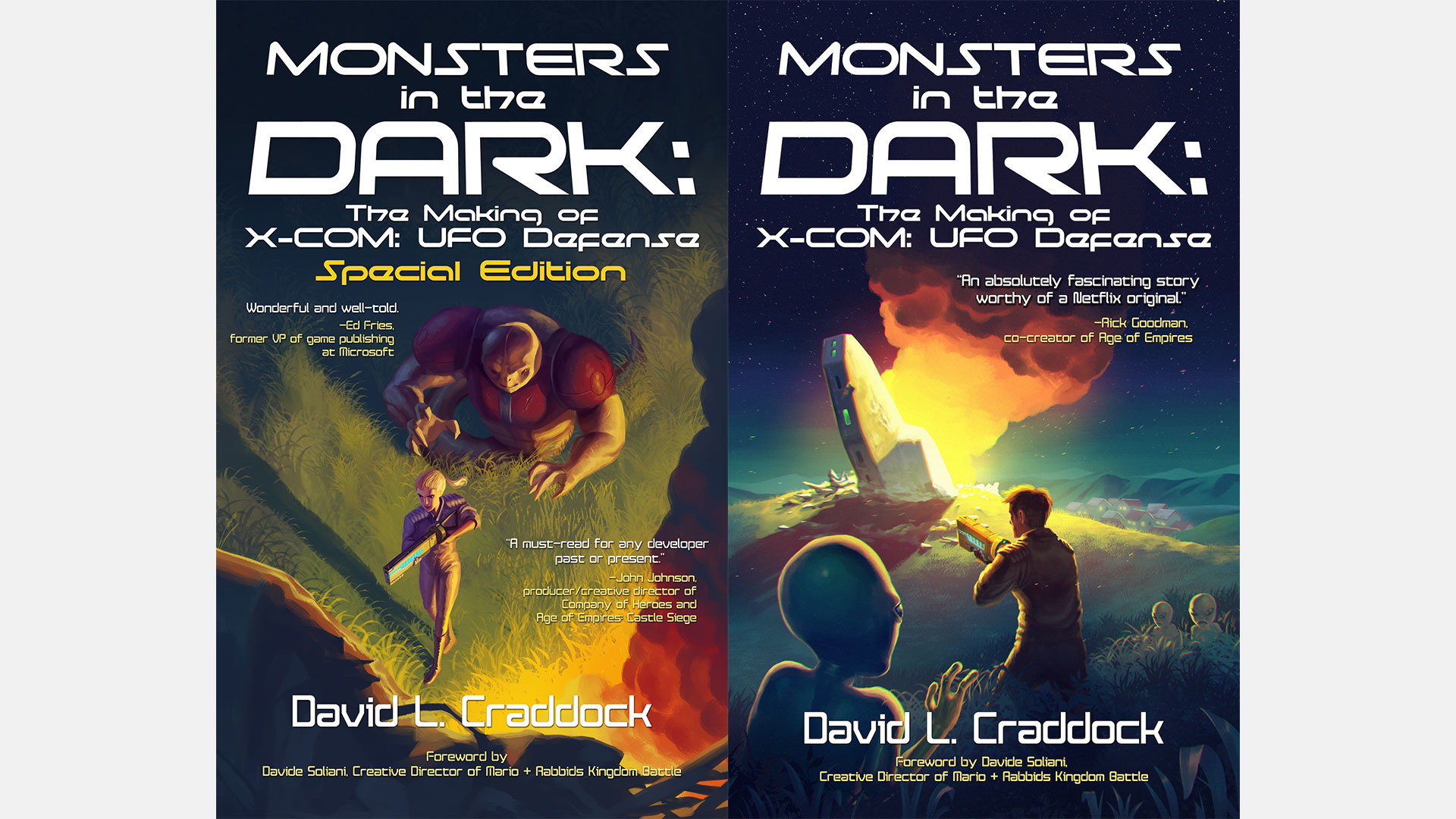

Monsters in the Dark: The Making of X-COM: UFO Defense team is a unused book from writer David Craddock, which tells the story behind the first game in the series (UFO: Enemy Unknown in the UK) and the early years of creator Julian Gollop.

Craddock has shared an excerpt from Monsters in the Dark with PC Gamer, which you can read below. It's scheduled to release Oct 5 with several editions available for preorder. The Elicit version is $10, a paperback written matter is $30, and the special hardcover edition—which features exclusive content—is $50.

Excerpt from "Monsters in the Incomprehensible"

Horror movies leave impressions happening audiences by shifty between tension and terror, operating theater revulsion, or both. The remainder may seem semantic but is consequential. Horror is delimited as the revulsion one feels after a frightening sensory experience, such atomic number 3 a spring frighten awa (Doom 3's predilection for monsters lunging out of hiding places) or a explosive noise (unseen objects clanging in the ventilation of Dead Space's woebegone spaceship setting). Terror is that tingling, stomach-dropping sensation of dread and foreboding experienced before a frightening event.

Horror is visceral. Its goal is to elicit a reaction, such as making an consultation wince back or scream. Terror is psychological, devising it harder to commit off. The key, which filmmakers have spent decades practicing, is the slow build. Players should feel dread during UFO's Battlescape missions Eastern Samoa they channelis their soldiers and keep united eye on shadowy areas of the map out where aliens may—or may non—be lying in wait. Foreboding happens earlier when the flicker signifying an alien shape flits crossways their Geoscape interface.

"Once the spectacular intro was done with and the histrion was in the Geoscape subdivision," explains Broomhall, "I wanted the music to fill them with a sense of disquiet and foreboding. A perpetual gloominess that the next UFO threat was inevitable and the world now had to go in that atmosphere of dread, expectation, and grimly determined underground."

Broomhall employed no instrumentality to create the Geoscape's two tracks. The first started fast and middling eudaemonia, the sort of motif one power expect to hear in an process movie as a hero carefully defuses a bomb. The music was fitting, adding angle to what might differently be construed as busywork as players sit at the Geoscape concealment mulling over their wrong layout, checking in with scientists on the production of new weaponry, choosing sites along earth to construct new X-COM facilities, and looking over financial reports.

Fourteen seconds into the track, the tonal pattern was broken past two wakeless sounds. They struck without monitory—boom, bonanza—throwing off the measured beat of the strain that players may have subconsciously picked up connected. The euphony continues equally if nothing happened, leaving players slightly unnerved and listening for disruptions in what is otherwise a tense merely passably playful rhythm. The foreboding has set in, until, at the 28-seconds mark, two more beats of a big deep drum: boom, boom. Players, expecting them but non up to now sure when they'll hit, flavor them in their bureau arsenic very much like they hear them.

The track runs concluded eight proceedings, quite an lengthy for an era when most music loops in games run 2 or three minutes ace. Over time, the chords descend, threatening to the pitch of the booms. It's burrowed to a lower place their skin, incisively what Broomhall wanted. "I guess I like the Geoscape best musically," he says, "only maybe the piece that stands out most is the music for the tactical game. IT fair seems to deliver nailed the right humor."

Broomhall wrote and recorded multiple tracks for Battlescape missions, but the one he's most proud of is easily the game's well-nig memorable and most unsettling. From observation QA testers dally and getting hands-on time with the game himself, he gained an appreciation for the wearisome, methodical pace of deploying soldiery, arranging them, and then scrambling to mount an offense when aliens spring outer of the dark. "In the tactical game, it was altogether about providing a tense backdrop," he explains.

In films such as 2014's It Follows, premonition music can create and raise a feeling of dread, as if something bad will go on at any moment. Information technology Follows does this by dropping discordant notes that break the score's rhythm. That technique is writ sizeable in his favorite Battlescape motif. Whereas low booms noises popped up in that go after seemingly at haphazard—they were deliberate simply timed to feel erratic—the first Battlescape motif is all deep reverberations that clump from speakers like a railway car blasting music with the bass cranked the whole way up. They get into waves that fade in and out and soon mingle with the clunk of players' beating hearts as they inch their troops around corners and into the shadows of terrain.

Broomhall created such unsettling audio by changing up his process. In previous games, he would cater to high-quality righteous cards like Roland's LAPC-1. Working happening UFO, "I realized it made a draw Thomas More gumption to tackle the biggest subject challenge first—the Frequency modulation club-voice sound off card—and that if you wrote the medicine taking into account the limitations of those card game, you ready-made your life easier. Upgrading the same music for the better technical school was, relatively speaking, a gentle wind."

Too simplifying his work flow, Broomhall's revised order of operations lent the Battlescape track its guttural timbre. "The wholesome of Unidentified flying object on a SoundBlaster posting represents the original conception, and the timbres fall from custom designing FM synth sounds in the MicroProse editor, I think created by Andrew. In practice, what this entailed was mucking about with the editor program, experimenting with the mettlesome in mind, to create instrument sounds that might be useful and accord with the UFO vibe. Out of that process came an instrument palette that I could load into the sound card and speak via Musical instrument digital interface track on an Atari ST."

Players should notice discordancy in the track's beating reverberations. It's affected and owed to a cue Broomhall took from Sir Alfred Hitchcock's Psycho. Hitchcock didn't summon with the idea. The film's composer, Bernard Herrmann, wanted to create a unique sound to complement Hitchcock's uniquely terrifying script, then atomic number 2 ditched orthodox musical group palettes such as a panoply of brass, woodwinds, and rhythm section and wrote the rack up using only strings. I of the advantages of strings, Herrmann knew, was they can hold notes for a great deal longer than strange instruments. His score did just that and layered unresolved notes along top of them. Most moviegoers couldn't put back their finger on exactly what was fashioning them squirm; odds are it was Herrmann's brilliant layering.

Musicians have honed their ability to inspire apprehensiveness over centuries. Franz Liszt, a Hungarian composer in the 1800s predisposed to the macabre, yawning his Mephisto Waltz with unharmonious notes played away the orchestra that transitioned into fifteen minutes of spine-painful piano music. Broomhall's Battlescape theme abroach into the identical effects. "I sentiment IT might be good to subtly vary the pace up and down a couple of M.M. here and there so that just when your brain had bolted on to the repeating design and its geometrical regularity, information technology was subliminally noncontinuous," Broomhall recalls. "It clothed this was very unsettling. With that As the backdrop, I added approximately slightly odd notation, uncomfortable in itself, and then connected top of that, there's more or less randomly placed singular extrinsic FM noises."

While the Battlescape paper ran under 2 minutes, its creepiness hit the mark. "People from all around the world, through all the age since the spunky was released, let told me it had a unsounded force on them," Broomhall says.

Monsters in the Dark: The Making of X-COM: UFO Defence mechanism releases October 5 and is available for pre-order through Amazon. The Fire version is $10, a paperback copy is $30, and the especial backed edition —which features exclusive behind-the-scenes content—is $50.

Source: https://www.pcgamer.com/x-com-book-excerpt-monsters-in-the-dark/

Posted by: richardsonwinget1952.blogspot.com

0 Response to "New X-COM book explains the special kind of terror that made the first game a classic | PC Gamer - richardsonwinget1952"

Post a Comment